Post by wren on Jan 23, 2007 16:02:59 GMT -5

"Merlin... walked warily around the stones. His lips moved without stay, as those of a man about his orisons [prayers], though I cannot tell whether or no he prayed. At length Merlin beckoned to the Britons. 'Enter Boldly!' cried he, 'There is naught to harm. Now you may lift these pebbles from their seat and bae and charge them on your ships.' So, at his word and bidding they wrought as Merlin showed them." (trans. Lewis Thorpe)

The stones were floated across the sea to Britain, where they are set up on the Plain of Amesbury. Nothing further is said about how this was achieved but whether Merlin made use of technical skills or magic the feat firmly established him as a wonder worker... ~taken from Merlin - Shaman, Prophet, Magician by John Matthews.

The stones were floated across the sea to Britain, where they are set up on the Plain of Amesbury. Nothing further is said about how this was achieved but whether Merlin made use of technical skills or magic the feat firmly established him as a wonder worker... ~taken from Merlin - Shaman, Prophet, Magician by John Matthews.

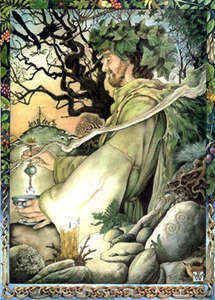

Apart from the celebrated tales of Mabinogion and other ancient remnants, the Welsh manuscripts are most notable for having preserved for us legends concerning – and poems supposed to have been written by – extraordinary figures of Celtic lore. One of the best known of these, Merlin needs little introduction. He is most stereotypically known from the Arthurian romances. The arch-wizard and counselor to the King, who confounded the court wizards of Vortigern while still a precocious child, continues to case his spell from his castle of glass into our own times. While it might be said that Merlin seems to be an archetypal Druid, it should be noted that many sources cast him also in the role of shaman-poet. It is indeed noteworthy that there is a strand of Celtic lore surrounding this figure which seems to be partially separate from the more judicious Druids; that of warrior shaman whose anarchic, even mad behavior may lead us into the deepest substratum of Celtic ‘nature’ religion. There is also food for thought here, as such figures as Merlin have associations with the great trees of Ogham lore.

Merlin and Vortigern

Myrddin Wylt

Merlin has many faces and more than one manifestation in history. Lovers of Arthurian romance will be familiar with the Myrddin Ambrosius – crystallized in Geoffrey of Monmouth’s ‘Historia Regum Britanniae’ (History of the Kings of Britain) of about 1135 – who lived ‘long ago in the reign of King Vortigern’, that is, from the mid-fifth century. But there is another figure haunting the fringes of the medieval romances who is more mysterious still. That is the Myrddin Wylt (Merlin the Wild) who, although historically of a slightly later period, evokes far more archaic resonances.

Geoffrey of Monmouth’s original ‘Vita Merlini’ (Live of Merlin) tells of this other Merlin, who is primarily a wildman of the woods, ecstatic shaman and poet. Out of Strathclyde in the lowlands of Scotland of the sixth to seventh centuries comes record of one Merlin the Briton, who is allied as counselor to his lord Gwendeleu against the cruel Rydderch. Gwendeleu is ruler of an essentially pagan kingdom and court defending itself against the Christianized Rydderch. When his lord is defeated and the court shattered, Merlin goes mad and flees to the forest of Kellydon where he lives the life of an outcast. To add insult to injury, Geoffrey has Ganieda, Merlin’s own sister, become Rydderch’s wife! Finally captured, Merlin is brought to court and, seeing a leaf in his sister’s hair, laughs sardonically. When Rydderch demands to know the cause of his mirth, Merlin informs him that she got that leaf lying under a tree with her over. The king then sets up certain proofs by which the soothsayer is to prove himself.

What is most fascinating in all of this is Merlin’s sojourn in the woods. It is in this phase of his strange, mythicized life that he utters the famous pieces known collectively as the ‘Prophecies of Merlin’. That Merlin, replete as he is with Druid-like characteristics, retreats into the forest is instructive in itself, for the forest grove is the site of the Druid rituals. As Lucan wrote, ‘they worship the gods in the woods without recourse to temples.' That he turns mad is also greatly significant. For the ‘madness’ of Merlin has clear parallels with the shamanistic ecstasy of initiates to the mysteries of Nature religions across Europe and beyond. It is a profoundly embedded theme in Irish literature too, as we shall see.

The Apple Tree

Probably the most famous prophecy attributed to Merlin is known as ‘The Apple Tree’. Although various portions of the poem are later grafts, the nucleus of the material is undoubtedly ancient and parts may be attributed to the shadowy figure of Myrddin Wylt himself. In ‘The Apple Tree’, Merlin laments his fate: exclusion from the court, poverty and want of human kindness. And, it is at the same time a lyrical celebration of the natural world, full of praise and wonder for forest, lake and mountain. Through all of this, Merlin’s only friend is the apple tree, under whose spreading branches he shelters, remembering his former life, and prophesying for the future. These fragments give an idea of the overall strain of the work.

Sweet apple tree, you of the lovely branches

Putting forth vigorous buds on all sides…

Sweet apple tree with yellow reflections,

You who grow on a hill above the moor…

Sweet apple tree of lush foliage,

I have fought beneath you to please a maiden…

Sweet apple tree that grows in the clearing…

Putting forth vigorous buds on all sides…

Sweet apple tree with yellow reflections,

You who grow on a hill above the moor…

Sweet apple tree of lush foliage,

I have fought beneath you to please a maiden…

Sweet apple tree that grows in the clearing…

Now, the apple has more than just naturalistic associations. It is also a grand gateway tree linked to the Otherworld. Its branch is the badge of the filé and its fruit are the apples of healing and immortality found in Avallach or Avalon, the island of apples to which Arthur is ultimately taken on his funeral barge.

Merlin here presents, in fact, the archetype of the shaman-poet, prophesying with the wisdom of the Otherworld. Like other sacrificial figures, such as Odin, Christ or the Buddha, he undergoes his great transformation beneath the branches of a gateway tree. And, in other Celtic sources, we find parallels to Merlin in the equally strange figures of Lailoken and Suibhné, demonstrating that Merlin himself is merely one manifestation of deeply imbedded cultural theme. The Lailoken referred to in the twelfth-century ‘Life of Saint Kerigern’ provides valuable corroboration of the widespread nature of the wildman storyline: he is banished to the wood, goes mad and from his rock prophesies bitterly. But it is in the legends associated with Suibhné, particularly as found in the twelfth-century ‘Buile Shuibni’ (The Frenzy of Suibhné), that we find the most illuminating parallels with the ecstasies and sufferings of Merlin.

The Madness of Suibhné

Suibhné of Argyll throws St. Rónán’s psalter into a lake, exhibiting a similar impatience with the new religion to that of the reprobate pagan Merlin. After some ongoing skirmishing, the saint curses Suibhné, who is gripped by madness and flees by air in the likeness of a bird. Spending seven years in woods in Glenn Bolcáin in Ireland, Suibhné prophesies and composes poetry. At the end of the seven years, he lives an entire year in a yew tree in Ros Ercáin. His son-in-law’s ministrations cure him briefly, but madness still grips him and he returns to the woods, climbs a tree and recalls his life in the forest, its trees, and the wild places of Ireland. He remains in the forest for sometime and, as conveniently foretold in Rónán’s prediction, does not live long after leaving it.

A number of elements in this tale are noteworthy. First is symbolic bird-flight (an ancient shamanistic theme), his ecstasy and his versifying. The year within a tree trunk is clearly ritualistic; as the Idho few of the Ogham associated with the yew shows, this is a tree of death and transformation, literal or symbolic. The recitation from a treetop is a classic shamanistic theme, derived from the ancient motif widespread across Europe and Asia of the shaman’s ascent of the World Tree into the upperworlds of the gods. What is more, as the verses below reveal, Suibhné’s poetry comes out in a type of magical formula, entwined with treelore. In the following lines, he elaborates the virtue of the trees of the wood, of the sacred grove:

Thou oak, bushy, leafy,

Thou art high beyond the trees;

O hazlet, little branching one,

O fragrance of hazel-nuts.

O alder, thou art not hostile,

Delightful is thy hue,

Thou art not rending and prickling

In the gap wherein thou art.

O little blackthorn, little thorny one;

O little black sloe tree;

O water cress, little green-topped one,

From the brink of the ousel spring.

O minen of the pathways,

Thou art sweet beyond herbs,

O little green one, very green one,

O herb which grows the strawberry.

O apple tree, little apple –tree,

Much are thou shaken;

O quicken, little berried one,

Delightful is thy bloom.

O briar, little arched one,

Thou grantest no fair terms,

Thou ceasest not to tear me,

Till thou hast thy fill of blood.

O yew-tree, little yew-tree,

In churchyards, thou are conspicuous;

O ivy, little ivy,

Thou art familiar in the dusky wood.

O holly, little sheltering one,

Thou door against the wind;

O ash-tree, thou baleful one,

Hand weapon of the warrior.

O birch, smooth and blessed,

Thou melodious, proud one,

Delightful each entwining branch

In the top of thy crown.

The aspen a-trembling;

By turns I hear

Its leaves a-racing –

Meseems ‘tis the foray!

My aversion in woods –

I conceal it not from anyone –

Is the leafy stick of the oak

Swaying evermore.

Thou art high beyond the trees;

O hazlet, little branching one,

O fragrance of hazel-nuts.

O alder, thou art not hostile,

Delightful is thy hue,

Thou art not rending and prickling

In the gap wherein thou art.

O little blackthorn, little thorny one;

O little black sloe tree;

O water cress, little green-topped one,

From the brink of the ousel spring.

O minen of the pathways,

Thou art sweet beyond herbs,

O little green one, very green one,

O herb which grows the strawberry.

O apple tree, little apple –tree,

Much are thou shaken;

O quicken, little berried one,

Delightful is thy bloom.

O briar, little arched one,

Thou grantest no fair terms,

Thou ceasest not to tear me,

Till thou hast thy fill of blood.

O yew-tree, little yew-tree,

In churchyards, thou are conspicuous;

O ivy, little ivy,

Thou art familiar in the dusky wood.

O holly, little sheltering one,

Thou door against the wind;

O ash-tree, thou baleful one,

Hand weapon of the warrior.

O birch, smooth and blessed,

Thou melodious, proud one,

Delightful each entwining branch

In the top of thy crown.

The aspen a-trembling;

By turns I hear

Its leaves a-racing –

Meseems ‘tis the foray!

My aversion in woods –

I conceal it not from anyone –

Is the leafy stick of the oak

Swaying evermore.

The trees in this poem correspond closely to the Ogham letters. Most importantly, they reveal to us yet again the essential story of the Druid or shaman reciting lore of the woodland, singing the praises of the denizens of the forest.

The Merlin/Lailoken/Suibhné figure seems to stem from the older and wider archetype of the wild man of the woods who learns the forest’s lore in a state of ecstasy. Shaman of the treetops and also master of the beasts whose many transformations include the horned figure of the stag, Merlin is an initiate into the mysteries of the goddess. This is the true meaning of his laughter at the leaf in his sister’s hair, for it is he who has lain with her under a tree, as Jean Markale demonstrated, based on the widespread underlying theme of sacred incest in these stories. Whatever the Freudian interpretation of this, in Celtic culture it relates to initiation into the mysteries of the goddess, just as Finn mac Cumhail tastes of the salmon of the water of the River Boyne (and thus the Mother Goddess Boánn after whom it is named) and the Welsh bard Taliesin becomes the grain of corn that impregnates Ceridwen, making him his own father. Incest here is being employed not literally but as a metaphor for ultimate union with the divine (the Mother Goddess), a transcendence of duality, and realization of absolute oneness. It is, in other words, masking a profound religious theme.

Breton legends regarding Merlin associate him intimately with a spring or ‘fountain’ at the center of a wood. The tree and the well are once again connected in Celtic thought, for the well lies at the center of the sacred grove. As the twelfth-century roman writer Chrétueb de Troyes describes it in his ‘Yves’, in the language of that later period:

"[Go] to a spring not far from here… You’ll see the spring boiling, although its colder than marble. It’s in the shade of the loveliest tree that Nature ever managed to create. It keeps its leaves the whole year round and doesn’t shed them, however hard the winter…”

The spring is the prototype of the sacred well and is linked to the chthonic aspects of the goddess. Merlin is the priest of the spring under a tree in whose branches the birds of the Otherworld sing: he is guardian of the well in the nemeton. This function makes him a powerful counselor, as is his spiritual consort: the mysterious otherworldly woman who tends the well.

References:

Chrétien de Troyes, ‘Arthurian Romances’, trans. D.D.R. Owen (London: Dent, 1987)

Markale, Jean, ‘Celtic Civilisation’, trans. Christine Hauch (London: Gordon and Cremonesi, 1978; originally published as ‘Les celtes et la civilisation celtique’, Paris:: Payot, 1976)